No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 393: | Line 393: | ||

The perfect nature is emptiness in the sense that what appears as other-dependent false imagination is primordially never established as the imaginary nature. As the ultimate object and the true nature of the other-dependent nature, this emptiness is the sphere of nonconceptual wisdom, and it is nothing other than phenomenal identitylessness. It is called "perfect," because it never changes into something else, is the supreme among all dharmas, and is the focal object of prajñā during the process of purifying the mind from adventitious stains. Since the dharmas of the noble ones are attained through realizing it, it is called "dharmadhātu." By virtue of its quality of never changing into something else, it is termed "suchness." Just as space, it is without any distinctions, but conventionally, the perfect nature may be presented as twofold—the unchanging perfect nature (suchness) and the unmistaken perfect nature (the nondual nonconceptual wisdom that realizes this suchness). At times, the perfect nature is also equated with the luminous nature of mind free from adventitious stains, or buddha nature. The ''Mahāyānasaṃgraha'' characterizes the three natures as follows: | The perfect nature is emptiness in the sense that what appears as other-dependent false imagination is primordially never established as the imaginary nature. As the ultimate object and the true nature of the other-dependent nature, this emptiness is the sphere of nonconceptual wisdom, and it is nothing other than phenomenal identitylessness. It is called "perfect," because it never changes into something else, is the supreme among all dharmas, and is the focal object of prajñā during the process of purifying the mind from adventitious stains. Since the dharmas of the noble ones are attained through realizing it, it is called "dharmadhātu." By virtue of its quality of never changing into something else, it is termed "suchness." Just as space, it is without any distinctions, but conventionally, the perfect nature may be presented as twofold—the unchanging perfect nature (suchness) and the unmistaken perfect nature (the nondual nonconceptual wisdom that realizes this suchness). At times, the perfect nature is also equated with the luminous nature of mind free from adventitious stains, or buddha nature. The ''Mahāyānasaṃgraha'' characterizes the three natures as follows: | ||

<blockquote>"In this . . . very extensive teaching of the mahāyāna . . ., how should the imaginary nature be understood?" It should be understood through the teachings on the synonyms of nonexistents. "How should the other-dependent nature be understood?" It should be understood to be like an illusion, a mirage, an optical illusion, a reflection, an echo, [the reflection of] the moon in water, and a magical creation. "How should the perfect nature be understood?" It should be understood through the teachings on the four kinds of pure dharmas. As for these four kinds of pure dharmas, (1) natural purity means suchness, emptiness, the true end, signlessness, and the ultimate. Also the dharmadhātu is just this. (2) Unstained purity refers to [the state of] this very [natural purity] not having any obscurations. (3) The purity of the path to attain this [unstained purity] consists of all the dharmas concordant with enlightenment, such as the pāramitās. (4) The pure object in order to generate this [path] is the teaching of the genuine dharma of the mahāyāna. In this way, since this [dharma] is the cause for purity, it is not the imaginary [nature]. Since it is the natural outflow of the pure dharmadhātu, it is not the other-dependent [nature either]. All completely pure dharmas are included in these four kinds [of purity].</blockquote> | <blockquote>"In this . . . very extensive teaching of the mahāyāna . . ., how should the imaginary nature be understood?" It should be understood through the teachings on the synonyms of nonexistents. "How should the other-dependent nature be understood?" It should be understood to be like an illusion, a mirage, an optical illusion, a reflection, an echo, [the reflection of] the moon in water, and a magical creation. "How should the perfect nature be understood?" It should be understood through the teachings on the four kinds of pure dharmas. As for these four kinds of pure dharmas, (1) natural purity means suchness, emptiness, the true end, signlessness, and the ultimate. Also the dharmadhātu is just this. (2) Unstained purity refers to [the state of] this very [natural purity] not having any obscurations. (3) The purity of the path to attain this [unstained purity] consists of all the dharmas concordant with enlightenment, such as the pāramitās. (4) The pure object in order to generate this [path] is the teaching of the genuine dharma of the mahāyāna. In this way, since this [dharma] is the cause for purity, it is not the imaginary [nature]. Since it is the natural outflow of the pure dharmadhātu, it is not the other-dependent [nature either]. All completely pure dharmas are included in these four kinds [of purity].<ref>II.26 (P5549, fol. 21a.5–21b.4). Note that Vasubandhu (P5551, fol. 180b.4–5) comments on the pure object (4) that, if it were the imaginary nature, it would have arisen from the cause of afflicted phenomena; and if it were the other-dependent nature, it would be something that is unreal.</ref></blockquote> | ||

As in this passage, many Yogācāra texts emphasize the unreal nature of the other-dependent nature and that it is definitely not the ultimate existent. Nevertheless, the other-dependent nature's lack of reality does not prevent the mere appearance and functioning of various seeming manifestations for the mind. The ''Mahāyānasaṃgraha'' continues: | As in this passage, many Yogācāra texts emphasize the unreal nature of the other-dependent nature and that it is definitely not the ultimate existent.<ref>See also below for Sthiramati's comments on verses 23–24 of Vasubandhu's ''Triṃśikā'' and his equating the other-dependent nature with the ''ālaya''-consciousness, which is eventually eliminated in its fundamental change of state.</ref> Nevertheless, the other-dependent nature's lack of reality does not prevent the mere appearance and functioning of various seeming manifestations for the mind. The ''Mahāyānasaṃgraha'' continues: | ||

<blockquote>Why is the other-dependent nature taught in such a way as being like an illusion and so on? In order to eliminate the mistaken doubts of others about the other-dependent nature. . . . In order to eliminate the doubts of those others who think, "How can nonexistents become objects?" it is [taught] to be like an illusion. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can mind and mental events arise without [outer] referents?" it is [taught] to be like a mirage. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can likes and dislikes be experienced if there are no referents?" it is [taught] to be like a dream. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can the desired and undesired results of positive and negative actions be accomplished?" it is [taught] to be like a reflection. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can various consciousnesses arise if there are no referents?" it is [taught to be] like an optical illusion. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can various conventional expressions come about if there are no referents?" it is [taught] to be like an echo. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can the sphere of the meditative concentration that apprehends true actuality come about?" it is [taught] to be like [a reflection of] the moon in water. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can unerring bodhisattvas be reborn as they wish in order to accomplish their activity for sentient beings?" it is [taught] to be like a magical creation.</blockquote> | <blockquote>Why is the other-dependent nature taught in such a way as being like an illusion and so on? In order to eliminate the mistaken doubts of others about the other-dependent nature. . . . In order to eliminate the doubts of those others who think, "How can nonexistents become objects?" it is [taught] to be like an illusion. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can mind and mental events arise without [outer] referents?" it is [taught] to be like a mirage. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can likes and dislikes be experienced if there are no referents?" it is [taught] to be like a dream. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can the desired and undesired results of positive and negative actions be accomplished?" it is [taught] to be like a reflection. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can various consciousnesses arise if there are no referents?" it is [taught to be] like an optical illusion. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "How can various conventional expressions come about if there are no referents?" it is [taught] to be like an echo. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can the sphere of the meditative concentration that apprehends true actuality come about?" it is [taught] to be like [a reflection of] the moon in water. In order to eliminate the doubts of those who think, "If there are no referents, how can unerring bodhisattvas be reborn as they wish in order to accomplish their activity for sentient beings?" it is [taught] to be like a magical creation.<ref>II.27 (ibid., fols. 21b.5–22a.4).</ref></blockquote> | ||

These passages also highlight that the template of the three natures is not so much an ontological model, but primarily a soteriological one. This is also expressed in the ''Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkārabhāṣya'' on XIX.77–78, which says that the realization of the three natures is the special realization of bodhisattvas. As Nguyen says: | These passages also highlight that the template of the three natures is not so much an ontological model, but primarily a soteriological one. This is also expressed in the ''Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkārabhāṣya'' on XIX.77–78, which says that the realization of the three natures is the special realization of bodhisattvas. As Nguyen says: | ||

<blockquote>The close association between ontology and soteriology is indeed one of the distinctive features of Buddhism as a whole, and a topic that was given a most thorough analytical treatment in the Yogācāra tradition. . . . In fact, from the perspective of Mahāyāna Buddhism in general and the Yogācāra School in particular, the realization of Reality in itself implies the attainment of enlightenment, that is, nirvana, or in other words, the attainment of buddhahood. This is because in Mahāyāna Buddhology, buddhahood is synonymous with Ultimate or True Reality. Put differently, within the Yogācāra world view, ontological realization is not different from soteriological attainment. Thus the realization of True Reality in this context is more than just an ontological insight into reality; it also carries broader implications and ramifications from the practical perspective of soteriology.</blockquote> | <blockquote>The close association between ontology and soteriology is indeed one of the distinctive features of Buddhism as a whole, and a topic that was given a most thorough analytical treatment in the Yogācāra tradition. . . . In fact, from the perspective of Mahāyāna Buddhism in general and the Yogācāra School in particular, the realization of Reality in itself implies the attainment of enlightenment, that is, nirvana, or in other words, the attainment of buddhahood. This is because in Mahāyāna Buddhology, buddhahood is synonymous with Ultimate or True Reality. Put differently, within the Yogācāra world view, ontological realization is not different from soteriological attainment. Thus the realization of True Reality in this context is more than just an ontological insight into reality; it also carries broader implications and ramifications from the practical perspective of soteriology.<ref>Nguyen 1990, 84–85.</ref></blockquote> | ||

This becomes even clearer when the three natures are also referred to as "lack of nature" and "emptiness." The ''Laṅkāvatārasūtra'' says: | This becomes even clearer when the three natures are also referred to as "lack of nature" and "emptiness." The ''Laṅkāvatārasūtra'' says: | ||

<blockquote>When scrutinized with insight,<br>Neither the dependent, nor the imaginary,<br>Nor the perfect [natures] exist.<br>So how could insight imagine any entity?</blockquote> | <blockquote>When scrutinized with insight,<br>Neither the dependent, nor the imaginary,<br>Nor the perfect [natures] exist.<br>So how could insight imagine any entity?<ref>II. 132 (verse 198; D107, fol. 172a.5–6).</ref></blockquote> | ||

The way in which ''Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra'' XI.50–51 speaks about the lack of nature of all phenomena in general sounds exactly like what is found in prajñāpāramitā or Madhyamaka texts: | The way in which ''Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra'' XI.50–51 speaks about the lack of nature of all phenomena in general sounds exactly like what is found in prajñāpāramitā or Madhyamaka texts: | ||

| Line 412: | Line 412: | ||

<blockquote>The lack of nature establishes,<br>With each one being the basis of the following one,<br>Nonarising, nonceasing,<br>Primordial peace, and parinirvāṇa.</blockquote> | <blockquote>The lack of nature establishes,<br>With each one being the basis of the following one,<br>Nonarising, nonceasing,<br>Primordial peace, and parinirvāṇa.</blockquote> | ||

More specifically, the ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra's'' seventh chapter speaks at length about the lack of nature in terms of characteristics, the lack of nature in terms of arising, and the ultimate lack of nature as representing the imaginary, other-dependent, and perfect natures, respectively. Asaṅga's ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtrabhāṣya'' says that this threefold lack of nature is taught as a remedy for four wrong ideas about the meaning of what is taught through the lack of nature in general. For example, it is a misconception to think that the lack of nature is mere nonexistence, or to believe that what is without nature cannot arise even as a mere appearance on the level of seeming reality. | More specifically, the ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra's'' seventh chapter speaks at length about the lack of nature in terms of characteristics, the lack of nature in terms of arising, and the ultimate lack of nature as representing the imaginary, other-dependent, and perfect natures, respectively. Asaṅga's ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtrabhāṣya'' says that this threefold lack of nature is taught as a remedy for four wrong ideas about the meaning of what is taught through the lack of nature in general. For example, it is a misconception to think that the lack of nature is mere nonexistence, or to believe that what is without nature cannot arise even as a mere appearance on the level of seeming reality.<ref>P5481, fols. 8b.7–9a.3.</ref> | ||

In its discussions on establishing the mahāyāna sūtras as the words of the Buddha, chapters 3 and 4 of Vasubandhu's ''Vyākhyāyukti'' not only defend the prajñāpāramitā sūtras against the charge of nihilism, but point out that these sūtras themselves criticize nihilism as the activity of māras and that their key notion "lack of nature" is not to be understood literally in the sense of nothing existing at all. Rather, it has to be interpreted in the correct way, which is accomplished through the threefold lack of nature as presented in the ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra''. In particular, the lack of nature of all phenomena must be clarified in this way in order to relinquish the extremes of superimposition and denial, that is, in order to (1) prevent childish beings from clinging to the existence of the imaginary nature and (2) prevent those who do not understand, when just the main points are being discussed, from clinging to the nonexistence of those phenomena whose nature it is to be inexpressible. When discussing the levels and modes of existence of what are described by the three natures themselves, the ''Vyākhyāyukti'' matches them with the framework of the two realities: | In its discussions on establishing the mahāyāna sūtras as the words of the Buddha, chapters 3 and 4 of Vasubandhu's ''Vyākhyāyukti'' not only defend the prajñāpāramitā sūtras against the charge of nihilism, but point out that these sūtras themselves criticize nihilism as the activity of māras<ref>For example, P5562, fols. 116b.7–117b.7 and 122a.7–123a.1.</ref> and that their key notion "lack of nature" is not to be understood literally in the sense of nothing existing at all. Rather, it has to be interpreted in the correct way, which is accomplished through the threefold lack of nature as presented in the ''Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra''.<ref>Ibid., fol. 123b.2–6 (from D106, fol. 34a.7–34b.3).</ref> In particular, the lack of nature of all phenomena must be clarified in this way in order to relinquish the extremes of superimposition and denial, that is, in order to (1) prevent childish beings from clinging to the existence of the imaginary nature and (2) prevent those who do not understand, when just the main points are being discussed, from clinging to the nonexistence of those phenomena whose nature it is to be inexpressible. When discussing the levels and modes of existence of what are described by the three natures themselves, the ''Vyākhyāyukti'' matches them with the framework of the two realities: | ||

<blockquote>It may be said, "The Bhagavat taught in the ''Pāramārthaśūnyatā[sūtra]'', 'Both karmic actions and their maturations exist, but an agent is not observable.' | <blockquote>It may be said, "The Bhagavat taught in the ''Pāramārthaśūnyatā[sūtra]'', 'Both karmic actions and their maturations exist, but an agent is not observable.'<ref>This quote is also found in the ''Abhidharmakośabhāṣya'' (Pradhan ed., p. 468.20–21).</ref> How is this [statement to be understood]―in terms of the ultimate or the seeming? . . . If it is in terms of the ultimate, how could all phenomena lack a nature? If it is in terms of the seeming, it should not be said that an agent is not observable, since an agent too exists on the level of the seeming." To start, [one needs to know] what this "seeming" and what the ultimate is. By virtue of this, one will know what exists on the level of the seeming and what exists ultimately. Some [śrāvakas] may say, "The seeming consists of names, expressions, designations, and conventions, while the specific characteristics of phenomena are the ultimate." However, in this case, since both karmic actions and their maturations exist as both names and specific characteristics, [whether they pertain to the ultimate or not] depends on one's concept of existence, [that is, on] how one asserts these two [―karma and maturation―as being either names or specifically characterized phenomena].</blockquote> | ||

<blockquote>I hold that a person is something that exists on the level of the seeming, but not as something substantial, because it is [just a] name that is labeled onto the skandhas. Karmic actions and their maturations exist substantially on the level of the seeming, but do not exist ultimately, because they are the objects of mundane cognition. [''Paramārtha'' means] being the object of the ultimate, because the ultimate (''parama'') is supramundane wisdom and it is the object (''artha'') of the latter. The specific characteristics of the [above] two [karmic actions and their maturations] are not the sphere of this [wisdom], since its sphere is the inexpressible general characteristic [that is suchness]. Here, you may wonder, "Is it mundane cognition or supramundane [wisdom] that represents valid cognition?" There is only one [ultimately valid cognition]―supramundane [wisdom]. Mundane cognition has divisions―being attained subsequently to supramundane [wisdom], it is not [ultimate] valid cognition. [Needless to say then that any] other [cognitions] are not valid cognition [either]. Thus, this accords with a verse of the Mahāsaṅghikas:</blockquote> | <blockquote>I hold that a person is something that exists on the level of the seeming, but not as something substantial, because it is [just a] name that is labeled onto the skandhas. Karmic actions and their maturations exist substantially on the level of the seeming, but do not exist ultimately, because they are the objects of mundane cognition. [''Paramārtha'' means] being the object of the ultimate, because the ultimate (''parama'') is supramundane wisdom and it is the object (''artha'') of the latter.<ref>This is the second from among three ways to understand ''paramārtha'' (for details, see below). In Yogācāra, usually, "mundane" and "supramundane" cognition or wisdom are understood as the perceptive modes during a bodhisattva's subsequent attainment and meditative equipoise, respectively.</ref> The specific characteristics of the [above] two [karmic actions and their maturations] are not the sphere of this [wisdom], since its sphere is the inexpressible general characteristic [that is suchness]. Here, you may wonder, "Is it mundane cognition or supramundane [wisdom] that represents valid cognition?" There is only one [ultimately valid cognition]―supramundane [wisdom]. Mundane cognition has divisions―being attained subsequently to supramundane [wisdom], it is not [ultimate] valid cognition. [Needless to say then that any] other [cognitions] are not valid cognition [either]. Thus, this accords with a verse of the Mahāsaṅghikas:</blockquote> | ||

<blockquote>Neither the eye, the ear, nor the nose is valid cognition,<br>Nor is the tongue, the body, or mentation valid cognition.<br>If these sense faculties were valid cognition,<br>Whom would the path of noble ones do any good?</blockquote> | <blockquote>Neither the eye, the ear, nor the nose is valid cognition,<br>Nor is the tongue, the body, or mentation valid cognition.<br>If these sense faculties were valid cognition,<br>Whom would the path of noble ones do any good?<ref>This is ''Samādhirājasūtra'' IX.23. </ref></blockquote> | ||

<blockquote>. . . If one speaks about "the seeming" and states that "what accords with afflicted phenomena is explained as flaws" and "what accords with purified phenomena is explained to be excellent" [and yet claims that] these are nothing but mere verbiage, how could one explain anything to be excellent, explain anything as a flaw, or actually accept any seeming phenomena without doubt? In other words, if these too were [utterly] nonexistent, how could [the Buddha] speak of existence on the level of the seeming? Through denying all afflicted and purified phenomena, one could not express anything, since one would not abide in [knowing] what is the case and what is not the case and moreover refute one's own statements.</blockquote> | <blockquote>. . . If one speaks about "the seeming" and states that "what accords with afflicted phenomena is explained as flaws" and "what accords with purified phenomena is explained to be excellent" [and yet claims that] these are nothing but mere verbiage, how could one explain anything to be excellent, explain anything as a flaw, or actually accept any seeming phenomena without doubt? In other words, if these too were [utterly] nonexistent, how could [the Buddha] speak of existence on the level of the seeming? Through denying all afflicted and purified phenomena, one could not express anything, since one would not abide in [knowing] what is the case and what is not the case and moreover refute one's own statements.</blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 14:16, 27 October 2020

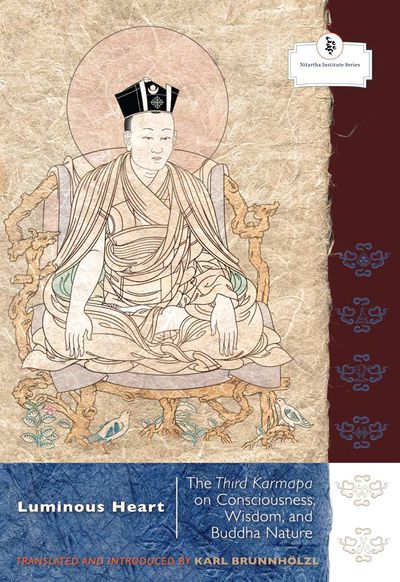

This superb collection of writings on buddha nature by the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339) focuses on the transition from ordinary deluded consciousness to enlightened wisdom, the characteristics of buddhahood, and a buddha’s enlightened activity. Most of these materials have never been translated comprehensively. The Third Karmapa’s unique and well-balanced view synthesizes Yogācāra, Madhyamaka, and the classical teachings on buddha nature. Rangjung Dorje not only shows that these teachings do not contradict each other but also that they supplement each other and share the same essential points in terms of the ultimate nature of mind and all phenomena. His fusion is remarkable because it clearly builds on Indian predecessors and precedes the later often highly charged debates in Tibet about the views of Rangtong ("self-empty") and Shentong ("other-empty"). Although Rangjung Dorje is widely regarded as one of the major proponents of the Tibetan Shentong tradition (some even consider him its founder), this book shows how his views differ from the Shentong tradition as understood by Dölpopa, Tāranātha, and the First Jamgön Kongtrul. The Third Karmapa’s view is more accurately described as one in which the two categories of rangtong and shentong are not regarded as mutually exclusive but are combined in a creative synthesis. For those practicing the sūtrayāna and the vajrayāna in the Kagyü tradition, what these texts describe can be transformed into living experience. (Source: Shambhala Publications)

| Citation | Brunnhölzl, Karl, trans. Luminous Heart: The Third Karmapa on Consciousness, Wisdom, and Buddha Nature. Nitartha Institute Series. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 2009. |

|---|---|

- An Aspiration by H.H. the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje8

- Foreword by H.H. the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje10

- Preface12

- Introduction15

- The Indian Yogācāra Background15

- The Tibetan Tradition on the Five Maitreya Texts119

- The Third Karmapa's View126

- Translations180

- The Autocommmentary on The Profound Inner Reality181

- The Ornament That Explains the Dharmadharmatāvibhāga241

- Four Poems by the Third Karmapa271

- Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé's Commentary on The Treatise on Pointing

Out the Tathāgata Heart288 - Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé's Commentary on The Treatise on the

Distinction between Consciousness and Wisdom366 - Karma Trinlépa's Explanation of the Sugata Heart447

- Appendix I: Pawo Tsugla Trengwa's Presentation of Kāyas, Wisdoms, and

Enlightened Activity463 - Appendix II: The Treatise on Pointing Out the Tathāgata Heart505

- Appendix III: The Treatise on the Distinction between Consciousness and

Wisdom517 - Appendix IV: Outline of NTC527

- Appendix V: Outline of NYC531

- Appendix VI: The Change of State of the Eight Consciousnesses into the Four

(Five) Wisdoms and the Three (Four) Kāyas534 - Glossary: English–Sanskrit–Tibetan536

- Glossary: Tibetan–Sanskrit–English542

- Bibliography548

- Endnotes589

The Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339), propounded a unique synthesis of Yogācāra, Madhyamaka, and the classical teachings on buddha-nature. His work occupies an important position between its Indian predecessors and the later, often highly charged debates in Tibet about "rangtong" (self-emptiness) and "zhentong" (other-emptiness). The Third Karmapa is widely renowned as one of the major proponents of the Tibetan zhentong tradition. This book contains a collection of some of his main writings on buddha-nature and the transition of ordinary deluded consciousness to enlightened wisdom.

An Aspiration by H.H. the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

You realize that whatever appears dawns within the play of the mind

And that mind itself is the dharmakāya free of clinging.

Through the power of that, you, the supreme siddhas, master apparent existence.

Precious ones of the Kagyü lineage, please bestow excellent virtue.

Through the heart of a perfect Buddha awakening in you,

You possess the blossoming glorious qualities of supreme insight.

You genuine holder of the teachings by the name Dzogchen Ponlop,

Through your merit, the activity of virtue,

You publish the hundreds of flawless dharma paintings

That come from the protectors of beings, the Takpo Kagyü,

As a display of books that always appears

As a feast for the eye of intelligence of those without bias.

While the stream of the Narmadā[1] river of virtue

Washes away the stains of the mind,

With the waves of the virtues of the two accumulations rolling high,

May it merge with the ocean of the qualities of the victorious ones.

This was composed by Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje as an auspicious aspiration for the publication of the precious teachings called The Eight Great Texts of Sūtra and Tantra by the supreme Dzogchen Ponlop Karma Sungrap Ngedön Tenpe Gyaltsen on April 18, 2004 (Buddhist Era 2548). May it be auspicious.

Foreword by H.H. the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje

In Tibet, all the ravishing and beautiful features of a self-arisen realm—being encircled by ranges of snow mountains adorned by superb white snowflakes and being filled with Sal trees, abundant herbs, and cool clear rivers―are wonderfully assembled in a single place. These wonders make our land endowed with the dharma the sole pure realm of human beings in this world. In it, all aspects of the teachings of the mighty sage, the greatly compassionate teacher skilled in means, are perfectly complete―the greater and lesser yānas as well as the mantrayāna. They are as pure and unblemished as the most refined pure gold; they accord with reasoning through the power of things; they dispel the darkness of the minds of all beings; and they are a great treasury bestowing all benefit and happiness one could wish for, just as desired. Not having vanished, these teachings still exist as the great treasure of the Kangyur, the Tengyur, and the sciences as well as the excellent teachings of the Tibetan scholars and siddhas who have appeared over time. Their sum equals the size of the mighty king of mountains, and their words and meanings are like a sip of the nectar of immortality. Headed by Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche with his utterly virtuous and pure intention to solely cherish the welfare of the teachings and beings, many dedicated workers of Nitartha international, striving with devotion, diligence, and prajñā, undertook hardships and made efforts over many years to preserve these teachings and further their transmission, and restore them. In particular, they worked toward the special purpose of propagating the excellent stream of teachings and practices of the unequaled Marpa Kagyü lineage, the great family of siddhas, in all directions and times, like the flow of a river in summertime. Through these efforts, the Eight Great Texts of Sūtra and Tantra publication series, inclusive of all the essential meanings of the perfectly complete teachings of the victor is magically manifesting as a great harvest for the teachings and beings. Bearing this in mind, I rejoice in this activity from the bottom of my heart and toss flowers of praise into the sky. Through this excellent activity, may the intentions of our noble forefathers be fulfilled in the expanse of peace.

Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje

Gyütö Ramoche Temple

July 19, 2002 (Buddhist Era 2547)

Preface

In an ongoing effort to create a body of English translations of essential works by the Karmapas and other major lineage figures of the Tibetan Karma Kagyü School, I present here a volume with some of the main writings of the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje[2] (1284–1339), on buddha nature, the origin and permutations of ordinary deluded consciousness, its transition to nonconceptual nondual wisdom, and the characteristics and functions of buddhahood together with its enlightened activity. These materials primarily include:

- Chapter 1 and excerpts from chapters 6 and 9 of The Profound Inner Reality with its autocommentary

- Pointing Out the Tathāgata Heart

- The Distinction between Consciousness and Wisdom

- Excerpts from The Ornament That Explains the Dharmadharmatāvibhāga'

In addition, this volume contains four shorter poems by the Third Karmapa:

- The Wisdom Lamp That Illuminates the Basic Nature

- Proclaiming Mind's Way of Being Mistaken

- Stanzas That Express Realization

- A Song on the Ālaya

These texts by the Third Karmapa are supplemented by:

- Two commentaries on Pointing Out the Tathāgata Heart and The Distinction between Consciousness and Wisdom by Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé[3] (1813–1899)

- Excerpts from a commentary by the First Karma Trinlépa, Choglé Namgyal[4] (1456–1539) on the first chapter of the autocommentary on The Profound Inner Reality

- Excerpts from Pawo Tsugla Trengwa's[5] (1504–1566) presentation of buddhahood, kāyas, wisdoms, and enlightened activity in his commentary on the Bodhicaryāvatāra.

As for the view of Karmapa Rangjung Dorje, this book may be regarded as a continuation of, and elaboration on, the remarks thereon in In Praise of Dharmadhātu (which also contains the Third Karmapa's commentary on this text), providing translations of more of the still-extant materials that describe his unique approach to both Yogācāra and Madhyamaka. In the Kagyü tradition, it is generally said that its distinct outlook on Madhyamaka was primarily presented by the Eighth Karmapa, Mikyö Dorje[6] (1507–1554), while its position on buddha nature (and the tantras) was mainly put forth by the Third Karmapa. As the following will show, the Yogācāra tradition of Maitreya, Asaṅga, and Vasubandhu may well be included in the scope of the Third Karmapa's explanations, which generally present a creative synthesis of Yogācāra, Madhyamaka, and the teachings on buddha nature. In addition, all of the above materials are not only scholarly documents, but bear great significance for practicing the Buddhist path and making what is described in them a living experience.

My wish to publish these texts in English dates far back, and the work on them has been in progress for about fifteen years, but had to be postponed many times due to other responsibilities, so I am truly delighted that this project finally comes to fruition. It would not have been possible without all the Tibetan masters from whom I received oral explanations on most of the above texts over the last two decades. In this regard, my heartfelt gratitude goes to Khenchen Tsultrim Gyamtso Rinpoche, Tenga Rinpoche, Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, Sangyé Nyenpa Rinpoche, Ringu Tulku, and the late Khenpo Lama Thubten. I am also very grateful to all the Western scholars, particularly Professor Lambert Schmithausen and Dr. Klaus-Dieter Mathes, who opened many doors to the Indian sources of the Yogācāra tradition.

Sincere thanks go to Sidney Piburn and Jeff Cox from Snow Lion Publications for their continuous support and readiness to publish this work, and to Michael Wakoff for being a meticulous and caring editor. I am also very grateful to Stephanie Johnston, who read through the entire manuscript, offered many helpful suggestions, and produced both the layout and the index. As for Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Tayé's commentary on Distinction between Consciousness and Wisdom, its first-draft translation was prepared together with Anna Johnson, Christine McKenna, Gelong Karma Jinpa, and Karma Chögyal during a three-month Tibetan Intensive at Gampo Abbey, Canada.

May this book be a contributing cause for the buddha heart of H.H. the Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Drodul Dorje swiftly embracing all sentient beings in whatever ways suitable. May it in particular contribute to planting and sustaining both the great scholarly and meditative traditions of the Karma Kagyü lineage in the English-speaking world, since they were founded and fostered by all the Karmapas as a means to introduce all beings into their true nature.

Fremont, Seattle, September 11, 2007

Introduction

The Indian Yogācāra background

In certain parts of the Eastern as well as the Western academic traditions, the Yogācāra School has often been neglected or misrepresented, usually in favor of assigning the "pole position" among Buddhist schools to Madhyamaka (in particular, to its Prāsaṅgika brand). There are many reasons for this, but two of the main ones are (1) making superficial and out-of-context judgments based on a unidimensional understanding and discussion of what seem to be stereotypical "buzz words" (such as cittamātra) and (2) not treating the concepts and explanations of Yogācāra in their own terms, but looking at them through the lenses of other philosophical systems. As Nguyen says:

It is a truism in modern studies of systems of meaning (such as cultures, languages, religions, mythology) that it is necessary first to see such a system of meaning from within, in terms of its own categories and concepts, and its own inherent logic. If on the contrary, we set out by attempting to view a system of meaning in terms of categories fundamentally alien to it, we are in danger of misconstruing the system and constructing a distorted interpretation of it that overlooks its basic meanings and inherent structure. This mistake has often been made in the past in studies of Yogācāra philosophy. . . .

In Buddhist literature itself, texts like the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra, Madhyāntavibhāga, and Mahāyānasaṃgraha are always careful to consider all particular concepts in their integral relationship to the thought-system as a whole. Each of these texts deserves careful study.[7]

Hall adds:

The argument over whether Vijñānavāda is idealistic or realistic bears a marked resemblance to the controversy as to whether Madhyamaka is nihilism or transcendental absolutism.

Mistaking taxonomy for understanding is a fault not limited to modern writers on Buddhism. A similar excessive concern for and trust in doctrinal labels can be seen in ancient Indian philosophers and Tibetan scholastics, and even in the Abhidharma itself. The identification of one school with another (such as that of Vijñānavāda with some Western form of idealism) is not only likely to be misleading; it is only all too often the point at which the argument stops. A more fruitful approach to comparative philosophy would begin by tentatively accepting several comparable philosophies as coherent systems in their own terms, and would proceed to apply their several viewpoints to specific problems of philosophy.[8]

As should be evidenced by many of the following quotes from Yogācāra texts, this school was definitely not advocating some kind of naïve idealism or psychologism, nor an ultimately and truly existing consciousness.[9] King says:

It should be made clear from the outset then that the Yogācāra school is far more complex in its understanding of the nature of experience than is usually acknowledged.[10]

Lusthaus elaborates:

Buddhism is not a psychologism. Even Yogācāra, which does propose to reduce karma and the entirety of the triple world to cognitive factors, is not a psychologism. This is because the point of Buddhist analysis is not the reification of a mental structure or theory of mind, but its erasure. Vasubandhu highlights the closure of cognitive horizons not because such a closure is either desirable or unalterable, but because the closure can only be opened once its all-encompassing complexity and ubiquity is understood and recognized. Yogācāra uses psychological arguments to overcome psychological closure, not to enhance it.[11]

The Yogācāras were also not immune or oblivious to notions such as "emptiness," "lack of nature," and "identitylessness" (which are often wrongly considered to belong solely and uniquely to Madhyamaka), but included and greatly used them as parts of their own explanations too. Specifically, hermeneutic frameworks such as the three natures, the threefold lack of nature, and the three emptinesses (see below) are not at all presented in order to contradict the prajñāpāramitā sūtras or Nāgārjuna, but equally serve to explain emptiness, just within a further developed hermeneutical system. As King says:

As a Mahāyāna school, the Yogācāra developed as a response to the insights of those same [prajñāpāramitā] sūtras. Under such circumstances, it would have been difficult indeed to have ignored the centrality of the notion of śūnyatā to these texts. In fact, the idea that the early classical Yogācāra of Asaṅga and Vasubandhu found any difficulty whatsoever in embracing the basic insights of the Madhyamaka school disregards both the historical and textual evidence, which, on the contrary, displays a spirit of underlying continuity and acceptance.[12]

However, in contrast to the Mādhyamikas' reluctance to speak about the specifics of seeming reality and the Buddhist path of purifying the deluded mind (or mind at all), the Yogācāra system, besides presenting sophisticated analyses of ultimate reality, also elaborates on how the deluded mind operates, how it can make the transition to the unmistaken wisdom that sees this mind's own ultimate nature, and what the characteristics and the fruition of this wisdom are. Thus, Yogācāra not only investigates the definitive meaning of the scriptures in a nonreifying manner, but also what happens experientially in the minds of those who study and practice this meaning. At the same time, it provides broader contextualizing comments on the sūtras and addresses typical misconceptions about emptiness and Madhyamaka, such as it being pure nihilism (which was a very common concern even among Buddhists since the time of Nāgārjuna). Consequently, one could even argue that the Yogācāra system is not only not inferior to the Madhyamaka approach, but exhibits a much more encompassing outlook on human experience and the soteriological[13] issues of the Buddhist path than the almost exclusively one-way deconstructive approach of the Mādhyamikas. This seems to have occurred already to some people in India, as the following verse attributed to the audience of the seven-year debate between Candragomī and Candrakīrti illustrates.

Ah, the treatises of noble Nāgārjuna

Are medicine for some and poison for others.

The treatises of Ajita[14] and noble Asaṅga

Are nectar for all people.[15]

King elaborates:

Thus, we find in the Yogācāra, as in the Madhyamaka school, a pointed refusal to become involved in an ontological debate. It is interesting that this type of analysis is something of a bridge-building exercise between what might be seen as an undue emphasis upon negative language (via negativa) in the exposition of emptiness by (some?) Mādhyamikas on the one hand, and the overarching realism (via positiva) of the Abhidharma schools on the other hand. As such, the Yogācāra movement can be seen as a "re-forming" of the Middle Path. This is not to say that such a reformation is necessarily out of step with the understanding of śūnyatā as systematized in the śāstras of Nāgārjuna (who is clearly neither a nihilist nor a realist in the accepted senses of the terms), but merely that, in its emphasis upon the "given" of meditative and so-called "normative" perception, the Yogācāra aim is to establish the appropriate parameters of linguistic usage and a rigorous logic for the establishment of the Mahāyāna position on experientially verifiable grounds.[16]

In addition, quite a number of Tibetan masters emphasize that Yogācāra (whether it is called that way or shentong) is more in harmony with the vajrayāna. For example, Śākya Chogden (1428–1507) says:

As for the reasonings that ascertain all phenomena as lacking a nature, the other one [that is, Niḥsvabhāvavāda] is vaster, while the [description of] the definitive meaning of what is to be experienced through meditation is more profound in this system. Because its explanation of nothing but nondual wisdom as what is to be experienced as a result of meditation very greatly accords with the vajrayāna [systems], this [latter] system is more profound.[17]

and

In the uncommon texts of mantra,

There is no explanation whatsoever

About what is to be experienced through the view

That is not in accord with the texts of Maitreya.[18]

. . .

The Maitreya dharmas accord with the mantra[yāna],

Because they assert solely nondual wisdom

As what is to be realized after [all] phenomena

In terms of apprehender and apprehended have been realized to be empty.

For all these reasons, let alone the Buddhist perspective proper, Yogācāra presentations of mental processes also have great potential to significantly contribute to the modern cognitive sciences. Nguyen suggests:

In modern studies of comparative philosophy and religion, Yogācāra thought, once adequately understood, should provoke major interest, given its startling parallels with the most modern developments in Western thought about cognition and epistemology. Just as the modern researchers now acknowledge that the modern world has much to learn from the medical lore of traditional cultures, the same could be said of classical Buddhist philosophical pyschology.[19]

In sum, the Yogācāra tradition considered itself as a continuation of all the preceding developments in Buddhism and not as a radical departure from them or even as a distinct new school per se. To retain what was regarded as useful in other schools of Buddhism did not mean to be ignorant of the pervasive Madhyamaka cautions against reifications of any kind. Thus, the vast range of Yogācāra writings represents a digest of virtually everything that previous Buddhist masters had developed, including intricate abhidharma analyses, charting the grounds of the many levels of the paths in the three yānas, subtle descriptions of meditative processes, presentations of epistemology and reasoning, explorations of mind and its functions in both its ignorant and enlightened modes, and commentaries on major mahāyāna sūtras. Thus, any linear or one-dimensional presentation of this Buddhist school seems not only misguided, but highly inconsiderate, due to the rich variety of this school’s sources and explanatory models (in itself, this variety and its development are nice examples of key Yogācāra notions, which usually describe processes rather than states or things). Nevertheless, a brief overview, in the Yogācāra School's own terms, of the main topics addressed in the following texts by the Third Karmapa is indispensable to demonstrate how firmly he is steeped in the view and explanations of this school.

The Major Yogācāra Masters and Their Works

Let's begin with the Indian masters (in roughly chronological order) and their major texts[20] that are at the core of the Yogācāra tradition. First and foremost, we have Maitreya and his five seminal works, which are the foundations for all subsequent Yogācāra scriptures:

- Abhisamayālaṃkāra[21]

- Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra[22]

- Madhyāntavibhāga

- Dharmadharmatāvibhāga

- Ratnagotravibhāga (Uttaratantra)[23]

Nāgamitra (third/fourth century?) composed a Kāyatrayāvatāramukha, which discusses dharmakāya, sambhogakāya, and nirmāṇakāya in terms of the three natures.

Asaṅga and Vasubandhu (both fourth century CE) were the two earliest commentators on the five texts by Maitreya and also composed many texts of their own. The following main Yogācāra texts are attributed to Asaṅga:

- Saṃdhinirmocanasūtravyākhyāna (commentary)

- Ratnagotravibhāgavyākhyā (commentary)[24]

- Yogācārabhūmi (consisting of the Bahubhūmivastu, Viniścayasaṃgrahaṇī, Vivaraṇasaṃgrahaṇī, Paryāyasaṃgrahaṇī, and Vastusaṃgrahaṇī)

- Abhidharmasamucchaya

- Mahāyānasaṃgraha

Vasubandhu's main Yogācara works consist of:

- Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkārabhāṣya

- Madhyāntavibhāgabhāṣya

- Dharmadharmatāvibhāgavṛtti

- Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya[25]

- Viṃśatikākārikā

- Triṃśikākārikā

- Trisvabhāvanirdeśa

- Karmasiddhiprakaraṇa

- Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇa

- Vyākhyāyukti

Guṇabhadra (394–468) was greatly active in translating and teaching mahāyāna sūtras as well as Yogācāra and tathāgatagarbha[26] materials in China. He is credited with the first translation of the Laṅkāvatārasūtra.

Dignāga (c. 480–540) is said to have taught at the Indian Buddhist University of Nālandā and is mainly famous for his logico-epistemological texts. However, as many studies have shown, these works (such as the Pramāṇasamucchaya) are generally grounded in the Yogācāra system. In addition, he also wrote a few more explicitly Yogācāra texts, such as the Ālambanaparīkṣā with its autocommentary.[27]

Ratnamati (fifth–sixth century) was another Indian active in China, who greatly emphasized the tathāgatagarbha teachings. He translated the Uttaratantra, Vasubandhu's commentary on the Daśabhūmikasūtra, and many other such texts.

Bodhiruci's collaboration with Ratnamati (and Buddhasānta) in translating Vasubandhu's above commentary came to an end over their disagreement as to whether tathāgatagarbha represents classical Yogācāra thought or not. Bodhiruci translated thirty-nine texts into Chinese, among them the Laṅkāvatārasūtra, the Anūnatvāpūrṇatvanirdeśasūtra, and the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.

Kambala (also fifth–sixth century) wrote a brilliant poetic treatise, called Ālokamālāprakaraṇanāma, which represents an unusually early and unique approach of synthesizing Madhyamaka and Yogācāra. Combining the framework of the three natures with that of the two realities, Kambala clearly assimilates Madhyamaka to Yogācāra and not vice versa (as, for example, Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla did much later). Also the autocommentary on his Bhagavatīprajñāpāramitānavaślokapiṇḍārtha (better known as Navaślokī) exhibits typical Yogācāra features.

Guṇamati (sixth century) wrote a commentary on Vasubandhu's Vyākhyāyukti and is renowned as Sthiramati's main teacher. Both were active at the Buddhist University of Valabhi (in present-day Gujarat).

Sthiramati (c. 510–570) is often unduly ignored, but he not only composed important commentaries on several of the above texts by Maitreya, Asaṅga, and Vasubandhu, but also systematized and elaborated many classical Yogācāra themes. Especially his large commentaries on Maitreya's Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra and Madhyāntavibhāga as well as his shorter one on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā can be considered as landmarks in Yogācāra writing in their own right. His Yogācāra works include:

- Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāravṛttibhāṣya

- Madhyāntavibhāgaṭīkā

- Viṃśatikābhāṣya

- Triṃśikābhāṣya

- Abhidharmasamucchayavyākhyā[28]

- Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇavaibhāsa

Paramārtha (499–569) traveled to China in 546 and remained there until the end of his life, being the first one to widely teach and translate Yogācāra (and tathāgatagarbha) materials there. The Chinese canon contains thirty-two texts attributed to him, either works authored by him or translations (partially with significant embedded comments). The latter include several sūtras, Asaṅga's Viniṣcayasaṃgrahaṇī and Mahāyānasaṃgraha, Vasubandhu's Madhyāntavibhāgabhāṣya and Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya (Paramārtha's most complex and significant work), and Vasubandhu's Viṃśatikā and Triṃśikā.[29] He also translated, if not authored, the famous Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna.[30] In addition, he is considered as the author (or at least the commentator and redactor) of the Buddhagotraśāstra (Fo Xing Lun),[31] which is one of the rare texts that synthesizes explicitly and in detail many classical Yogācāra materials, such as the three natures, with the notion of tathāgatagarbha. Among Paramārtha's novel interpretations of Yogācāra concepts, the best known is his theory of a ninth consciousness, called amalavijñāna (see below). This is primarily found in his commentary on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā, called Evolution of Consciousness (Chuan Shi Lun),[32] and the comments embedded in his translations of the Viniṣcayasaṃgrahaṇī, the Mahāyānasaṃgraha, and its Bhāṣya.[33] Together with Kumārajīva (344–413) and Hsüan-tsang (602–664), he is considered to be one of the greatest translators of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.[34]

Dharmapāla (530–561) was an abbot of Nālandā University. His works are only extant in Chinese, and Hsüan-tsang, who was instrumental in bringing Yogācāra teachings to China, greatly relies on Dharmapāla's views (primarily in his Vijñaptimātratāsiddhi, which compiles the commentaries by ten Indian Yogācāras on Vasubandhu's Viṃśatikā and Triṃśikā). Dharmapāla also composed a commentary on Dignāga's Ālambanaparīkṣā and had a famous written debate with Bhāvaviveka, which is found in the former's commentaries on Āryadeva's Catuḥśataka and Śataśāstra from a Yogācāra point of view.

Another sixth-century Yogācāra is Asvabhāva, who often closely follows Sthiramati and wrote the following commentaries on texts by Maitreya, Asaṅga, and Kambala:

- Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāraṭīkā

- Mahāyānasaṃgrahopanibandhana

- Ālokamālāṭīkāhṛdānandajananī

Śīlabhadra (529–645) followed Dharmapāla as the abbot of Nālandā and taught Hsüan-tsang for fifteen months during the latter's stay there. He is the author of the Buddhabhūmivyākhyāna, one of two extant commentaries on the Buddhabhūmisūtra (the other one being the Buddhabhūmyupadeśa).[35] His text greatly relies on the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra and its Bhāṣya, as well as on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.'

Guṇaprabha (sixth century) is of course most famous for his Vinayasūtra, but he also wrote a commentary on the Bodhisattvabhūmi, a Bodhisattvabhūmiśīlaparivartabhāṣya, and a commentary on Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇa.

Jinaputra (second half of sixth century) wrote a commentary on the Abhidharmasamucchaya and a short part of the Yogācārabhūmi, called Bodhisattvabhūmiśīlaparivartaṭīkā.

Prasenajit (sixth/seventh century) is reported to have studied with Sthiramati, Śīlabhadra, and many other masters, being highly erudite in all Indian Buddhist and non-Buddhist fields of knowledge. However, he preferred to live as a hermit outside of the Buddhist institutional mainstream and repeatedly refused to become the personal teacher of the then king of Magadha, instead dwelling with many hundreds of students on a mountainside. Though he is not known to have composed any texts of his own, he was highly influential in teaching Hsüan-tsang a great number of both Madhyamaka and Yogācāra texts, particularly providing the final clarifications on the Yogācārabhūmi, for two years after the latter had been taught by Śīlabhadra. When Hsüan-tsang returned to Nālan'thereafter, he debated some Mādhyamikas and finally even composed a (lost) Sanskrit treatise in three thousand stanzas on Yogācāra and Madhyamaka not being mutually exclusive, but in harmony.[36]

Candragomī (sixth/seventh century) was a disciple of Sthiramati. In his early adulthood, he had been married to a princess, but left her to spend the rest of his life keeping the five Buddhist precepts of a layman. He was very erudite in all Buddhist and non-Buddhist fields of learning and also a great poet. After being invited to Nālandā by Candrakīrti, he had an ongoing debate with the latter for seven years, defending the Yogācāra view. His teachings are reported to have been focused mainly on the Daśabhūmikasūtra, the Laṅkāvatārasūtra, the Samādhirājasūtra, the Gaṇḍālaṃkāradhāraṇī, and the prajñāpāramitā sūtras, of which he also composed synopses. Among his works, the most famous are the Candravyākaraṇa (a work on Sanskrit grammar), the Śiṣyalekha, and the Bodhisattvasaṃvaraviṃsaka (a mnemonic summary of the Ethics chapter of the Bodhisattvabhūmi). Many other texts by him (such as a *Pradīpamālā on the stages of the bodhisattva path) are mentioned in various sources, with some of them being more specifically Yogācāra, but none of them have survived.[37]

Dharmakīrti (c. 600–660), like Dignāga, is best known for his contributions to epistemology and logic through his seven texts on valid cognition (such as the Pramāṇavārttika), but these texts also clearly exhibit many Yogācara traits.

Vinītadeva (c. 645–715) composed commentaries on Vasubandhu's Viṃśatikā and Triṃśika and Dignāga's Ālambanaparīkśā (as well as on several of Dharmakīrti's treatises on valid cognition).

Pṛthivībandhu (seventh century?) wrote a detailed commentary on Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandhaprakaraṇa.

Jñānacandra (eighth century) composed a brief meditation manual, called Yogacaryābhāvanātātparyārthanirdeśa, and a commentary on Nāgamitra's Kāyatrayāvatāramukha.

Sāgaramegha (eighth century) wrote a massive commentary on the Bodhisattvabhūmi, called Yogācārabhūmaubodhisattvabhūmivyākhyā.

Sumatiśīla (late eighth century) authored a detailed commentary on Vasubandhu's Karmasiddhiprakaraṇa.

Late Yogācāras (all tenth–eleventh century) include Dharmakīrti of Sumatra[38] (one of the main teachers of Atiśa); Jñānaśrīmitra (Sākarasiddhi, Sākarasaṃgraha, and Sarvajñāsiddhi); Ratnakīrti (Ratnakīrtinibandhāvalī and Sarvajñāsiddhi); and Jñānaśrībhadra (commentary on the Laṅkāvatārasūtra, summary of the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra, and commentary on the Pramāṇavārttika). Ratnākāraśānti is variously considered a Yogācāra or Mādhyamika. In any case, most of his works (such as Vijñaptimātratāsiddhi, Triyānavyavasthāna, Madhyamakālaṃkāravṛtti-Madhyamapratipadāsiddhi, Prajñāpāramitopadeśa, and Madhyamakālaṃkāropadeśa) exhibit a synthesis of both these systems, often referred to as "Vijñapti-Madhyamaka."[39]

Several other Indian Mādhyamikas, such as Śrīgupta (seventh century?), Śāntarakṣita, Kamalaśīla, Haribhadra (all eighth century), Viydākaraprabha (eighth/ninth century), Jetāri (tenth/eleventh century), and Nandaśrī, indeed used a lot of Yogācāra materials, but clearly upheld the Madhyamaka view as their final position.

In brief, the main classical Indian exponents of Yogācāra are no doubt Maitreya, Asaṅga, Vasubandhu, and Sthiramati. As will be seen in the following, it is also primarily their works that provide the roadmap for the discussions of the eight consciousnesses, the four wisdoms, the three kāyas, and buddha nature in the Third Karmapa's texts translated below.

In terms of its contents, it should be noted that the Yogācāra system is by no means some kind of speculative philosophy that starts from a priori axioms and then constructs a magnificent edifice of abstract concepts in order to define what is true. On the contrary, the Yogācāra School proceeds from observing and analyzing a wide range of meditative experiences (hence its name), which reveal both the deluded and nondeluded processes of the mind. Through exploring and outlining the perceptual and conceptual structures of such processes, the Yogācāra system works out primarily their epistemological and soteriological implications (and only secondarily their ontological ones). As common in the Buddhist tradition (and many Indian spiritual traditions in general), Yogācāra treats epistemological analysis (a purely philosophical discipline for Western minds) as inseparable from, and being most relevant for, soteriological concerns (a religious matter for Western minds). In other words, the delusion about a truly existent self and phenomena and its resultant suffering are basically taken to be a cognitive error, while liberation or buddhahood is nothing but the removal of this error. As Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra VI.2 says:

In itself, the view about a self lacks the characteristic of a self,

As do its deformities―their characteristics differ [from a self].

Nor is there another [self] apart from these two, so it arises as a mere error.

Therefore, liberation is the termination of this mere error.

Vasubandhu's Bhāṣya and Sthiramati[40] comment that neither "the view about a self" (the mind that entertains the various beliefs related to "me" and "mine") nor its "deformities" (the five skandhas produced by afflictions and impregnations of negative tendencies) have the characteristics of a self, since their characteristics differ from those of a self, which on their view is purely imaginary (both the grasping at a self and the skandhas are multiple, conditioned, impermanent, not all-pervading, and so on, while the self is said to have the opposite characteristics). Nor is there a self outside of this grasping and the skandhas. Therefore, such grasping is nothing but an error, just as is mistaking a rope for a snake. And since there is no self that is in bondage, liberation is simply the termination of this error—there isn't anybody or anything that is liberated. Madhyāntavibhāga I.4 agrees, saying that liberation is nothing but the extinction of the false imagination that does not exist as it appears, yet seemingly exists and operates within a mind that is ignorant about its own true nature, in the form of projecting the fundamentally delusive duality of subject and object, upon which we then act.

The following is a brief outline of some of the main Yogācāra notions and pedagogic templates that are employed toward the end of terminating mind's self-delusion and revealing its natural state.

Continued here

The World Is Merely Mind's Own Play

One of the most inclusive notions in Buddhism in general and Yogācāra in particular is vikalpa (Tib. rnam rtog), with the related kalpanā (Tib. rtog pa), parikalpa (Tib. kun rtog), and their cognates. All of them have the basic sense of "constructing," "forming," "manufacturing," or "inventing." Thus, in terms of mind, they mean "creating in the mind," "forming in the imagination," and even "assuming to be real," "feigning," and "fiction." This shows that their usual translation as "thought" or "concept" is not wrong, but―particularly in a Yogācāra context―far too narrow. Fundamentally—and this is to be kept in mind throughout Buddhist texts—these terms refer to the continuous, constructive yet deluded activity of the mind that never tires of producing all kinds of dualistic appearances and experiences, thus literally building its own world.[41] Obviously, what is usually understood by "conception" or "conceptual thinking" is just a small part of this dynamic, since, from a Buddhist point of view, vikalpa also includes nonconceptual imagination and even what appears as outer objects and sense consciousnesses—literally everything that goes on in a dualistic mind, be it an object or a subject, conscious or not.[42] Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā 20–21ab says:

Whichever entity is imagined

By whichever imagination

Is the imaginary nature,

Which is unfindable.

But the other-dependent nature

Is the imagination that arises from conditions.

The meaning of "imagination" as an essentially deluded, dualistic, and illusory mental activity is particularly highlighted by the classical Yogācāra terms abhūtaparikalpa ("false imagination," lit. "imagination of what is unreal")[43] and parikalpita ("the imaginary," one of the three natures), with the latter being everything that appears as the division into subject and object that is produced by false imagination. The following passages serve to identify what false imagination is and its extent. For example, Madhyāntavibhāga I.8ab says:

False imagination [consists of]

The minds and mental factors of the three realms.

Vasubandhu's Madhyāntavibhāgabhāṣya on I.1 states:

Here, false imagination is the imagination of apprehender and apprehended.[44]

Sthiramati's Ṭīkā elaborates on this:

False imagination means that duality is unreal (or false) in it, or that [duality] is imagined by it. The word "false" indicates that it does not exist as it imagines [itself] in the form of being apprehender and apprehended. The word "imagination" indicates that referents are not found as they are imagined. Thus, being free from apprehender and apprehended is explained to be the characteristic of this [false imagination]. So, what is this [false imagination]? Without further differentiation, false imagination consists of the minds and mental factors of past, present, and future, which serve as causes and results, comprise the three realms, are beginningless, terminated by nirvāṇa, and conform with saṃsāra. But when differentiated, it is the imagination of the apprehender and the apprehended. Here, the imagination of the apprehended is consciousness appearing as [outer] referents and sentient beings. The imagination of the apprehender is consciousness appearing as a self and cognition. "Duality" refers to apprehender and apprehended, with the apprehended being forms and so on, and the apprehender being the eye consciousness and so on.[45]

Rongtön Shéja Künrig's[46] (1367–1449) commentary on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra explains:

All the many kinds of conceptions that are mentioned in the scriptures are included in false imagination, because they have the aspects of the three realms appearing as the duality of apprehender and apprehended under the sway of latent tendencies. False imagination is threefold―the conceptions that are the mere appearance as the duality of apprehender and apprehended; those that have the aspect of coarse states of mind; and those that have the aspect of the appearance of terms and their referents. The first consists of the mere appearance, under the sway of latent tendencies, of apprehender and apprehended being different. The second is what the abhidharma explains as the confused mental chatter that is included in the portions of [the mental factors of] intention and prajñā. The third is the clinging to referents through following names.[47]

In sum, this means that "imagination" includes all eight consciousnesses with their accompanying mental factors as well as their respective objects. As for all of this appearing, but actually being unreal, the mind's own confused play, Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra XI.15 states:

False imagination is explained

To be just like an illusion.

Just as the aspect in which an illusion [appears],

It is explained as the mistakenness of duality.

The Bhāṣya adds that false imagination should be known to be the other-dependent nature, which is also stated in XI.40cd. Furthermore, verses 4–5 of the Triṃśikā declare:

What appears here? The imagination of what is nonexistent.[48]

How does it appear? By way of having the character of duality.

What is its nonexistence with that [duality]?

The very nature of nonduality in it.

What is the imagination of the nonexistent here?

It is the mind that imagines in certain ways what [does not exist],

[But its] referents, which it imagines like that,

Are absolutely never found in these ways.

Sometimes, the opposite of false imagination―correct imagination―is also presented. The latter refers to the mind being engaged in cultivating the antidotes for false imagination on the Buddhist path. "Correct imagination" refers to increasingly more refined—but still more or less dualistic—mental processes or creations that serve as the remedies for respectively coarser kinds of obscuring mental creations, perceptions, and misconceptions (false imagination). Initially, on the paths of accumulation and preparation, such remedial activities are conceptual in a rather obvious way, such as meditating on the repulsiveness of the body as an antidote against desire, or cultivating bodhicitta through contemplating the kindness of one's parents and so on. More subtle approaches would include familiarizing with momentary impermanence or personal and phenomenal identitylessness. From the path of seeing onward, all coarse conceptions of ordinary sentient beings (even the remedial ones) have ceased. However, during the first seven bhūmis, there are still subtle concepts about true reality, and on the last three bhūmis, about attaining the final fruition of buddhahood. In other words, though phenomena are not taken as real anymore, on the first seven bhūmis, there is still the apprehending of characteristics, and on the last three bhūmis, there is still a subtle tendency of duality. In brief, since the remedial wisdom that consumes what is to be relinquished still depends on what it relinquishes and still entails subtle reference points with regard to the dharmadhātu,[49] it must eventually and naturally subside too, once even its most subtle fuel (the apprehending of characteristics and duality) is burnt up. Using the example of washing a stained shirt, remedial wisdom would correspond to the detergent used to wash away the stains. Obviously, after the detergent performed its function, both it and the stains would need to be removed from the shirt in order for it to be considered clean―from the perspective of the clean shirt itself, both stains and detergent are dirt. Thus, though correct imagination is the remedy for false imagination, both are still "imagination" in the sense that, from the perspective of the sole unmistaken cognition of a buddha, even the realizations on the bhūmis are not final and have to be transcended. As for the "nonconceptual wisdom" of buddhahood, it is the mind's ultimate cognitive capacity that is not impaired by any imaginations or mental fictions―in it, there is no delusional need or impulse to construct anything. Thus, a more literal rendering of the term would be "nonimaginative" or "nonconstructive" wisdom, whose facets or functions are the four wisdoms explained below.[50]

"Mind-Only?"

Everything being mind's imagination leads to the most well-known, but also most misunderstood notions of the Yogācāra School―cittamātra or vijñaptimātra. Very often, it is still said that these terms mean that outer objects do not exist and everything is "only mind," with "mind" being the only thing that really or ultimately exists. However, when looking at what the Yogācāra texts themselves say, this is a gross misrepresentation. The beginning of Vasubandhu's Viṃśatikāvṛtti says:

In the mahāyāna, the three realms are presented as being mere cognizance (vijñaptimātra). The sūtras say, "O sons of the Victor, all three realms are mere mind (cittamātra)." . . . Here, the word "mind" has the sense of [mind] being associated with [its mental factors]. "Mere" has the meaning of excluding referents.

All this is mere cognizance

Because of the appearance of nonexistent referents,

Just as the seeing of nonexistent strands of hair

In someone with blurred vision.

Like many other Yogācāra texts, Vasubandu's indeed continues by denying the existence of material outer objects, but the full purpose of teaching cittamātra is much vaster―realizing phenomenal identitylessness. Moreover, in this process, mere mind itself is no exception to being identityless. The Viṃśatikāvṛtti on verse 10 says:

How does the teaching on mere cognizance serve as the entrance to phenomenal identitylessness? It is to be understood that mere cognizance makes the appearances of form and so on arise, but that there is no phenomenon whatsoever that has the characteristic of form and so on. "But if there is no phenomenon in any respect at all, then also mere cognizance does not exist, so how can it be presented as such?" Entering into phenomenal identitylessness does not mean that there is no phenomenon in any respect at all. . . . It refers to the identitylessness in the sense of an imaginary identity, that is, a nature of phenomena as imagined by childish beings, which is the imaginary [nature, consisting of fictional identities] such as apprehender and apprehended. But it is not [meant] in the sense of [the nonexistence of] the inexpressible identity that is the object of the buddhas.[51] Likewise, one enters into the identitylessness of this very mere cognizance as well, in the sense of [it lacking] any identity imagined by yet another cognizance. It is for this reason that, through the presentation of mere cognizance, one enters into the identitylessness of all phenomena, but not through the complete denial of their [relative] existence. Also, otherwise, [mere] cognizance would be the referent of another cognizance, and thus [a state of] mere cognizance would not be established, since it [still] has a referent.[52]

Hall further comments on this as follows:

Vijñapti designates the basic phenomenon of conscious experience, without requiring its separation into object, subject, and act of cognition. . . . To translate vijñapti as "representation" conveys its "public" aspect, but seems to imply representation of something. . . . On the contrary, . . . when vijñapti is qualified as "vijñapti-only," it cannot be meant as a representation of anything else, especially not of an external object. . . . As is so often the case in Buddhist philosophy, Vasubandhu is consciously navigating between two extremes, which in this case may be called realism and idealism.

In negative terms, vijñapti-mātra rules out the realist extreme: substantial external objects of cognition are denied. However, vijñapti-mātra has also a positive connotation, and the fact that Vasubandhu here affirms precisely vijñapti ― rather than vijñāna or citta, which might be more easily misunderstood―seems to indicate an intent to avoid the idealist extreme as well. What is exclusively affirmed is not consciousness as an abiding entity, but the content of momentary acts of consciousness. When this vijñapti is equated with citta, manas, and vijñāna, it follows that mind itself is vijñapti-mātra: it consists of nothing else than the contents of momentary mental acts. The intention here is not to reduce the material to the mental, but to deny the dichotomy, while affirming that the basic reality is more usefully discussed in the terms belonging to a correct understanding of the mental.

. . . Vasubandhu points out that this teaching of dharma-nairātmya works only when vijñapti-mātra itself is understood to be vijñapti-only. Clearly, no reification of consciousness is intended here. . . .

The doctrine of vijñapti-mātra is not the metaphysical assertion of a transcendental reality consisting of "mind-only." It is a practical injunction to suspend judgment: "Stop at the bare percept; no need to posit any entity behind it."

Rather than asserting "mind-only" as the true nature of unconditioned reality, Vasubandhu presents "mind-only" as a description of our delusion: the dreams of this sleep from which the Buddha has awakened. It is, after all, saṃsāra that is declared to be vijñapti-mātra. Yet if "mind-only" is merely skepticism about reified external entities, how does it avoid the opposite extreme of reductionism? The world is neither completely real, nor completely unreal, but like a dream. A dream has its own presence and continuity, but its objects lack the substantiality of external objects. Whether common-sense things or Abhidharmic dharmas, dream-objects are bare percepts. If the dream-world saṃsāra is "mind-only" then freedom and the Buddhist path are possible―we can "change our minds." If the realms of meditation are "mind-only" then one can create a counter-dream within the dream of the world's delusion. Most important, one can awaken from a dream.[53]

Thus, that "mere mind" is being constantly referred to in Yogācāra texts as the delusional perception of what does not exist (these texts moreover abounding with dreams, illusions, and so on as examples for it) hardly suggests that said momentary mental activities exist in a real or ultimate way. In addition, Asvabhāva's Mahāyānasaṃgrahopanibandhana explicitly says that "mere mind" refers only to the mistaken minds and mental factors of saṃsāra (the realities of suffering and its origin), but not to the reality of the path:

As for [the statement in the sūtras], "[All three realms are] mere mind," "mind" and "cognizance" are equivalent. The word "only" eliminates [the existence of] referents, and by virtue of [such referents] not existing, [the existence of] an apprehender is eliminated too, because [both] are imaginary. [However,] since this [mind] does not arise without the mental factors, these mental factors are not negated. As it is said, "Without mental factors, mind never arises." . . . "All three realms" refer to cognizance appearing as the three realms. Through saying, "all three realms," it is held that the minds and mental factors that are associated with craving, such as desire, and contained in the three realms are just mere cognizance. However, this does not refer to [the minds and mental factors in meditative equipoise] that constitute the reality of the path (those that focus on suchness and those that focus on the other-dependent [nature]) and those during subsequent attainment. For, they are not made into what is "mine" through the cravings of engaging in the three realms, are remedies, and are unmistaken.[54]

Moreover, many Yogācāra works proceed by explicitly and repeatedly making it clear that "mere mind" does not exist and is to be relinquished in order to attain the full realization of buddhahood. For example, Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra VI.7–8 says:

Understanding that referents are mere [mental] chatter,

[Bodhisattvas] dwell in mere mind appearing as these.

Then, they directly perceive the dharmadhātu,

Thus being free from the characteristic of duality.

The mind is aware that nothing other than mind exists.

Then, it is realized that mind does not exist either.

The intelligent ones are aware that both do not exist

And abide in the dharmadhātu, in which these are absent.[55]

The Bhāṣya on these verses comments that, once bodhisattvas realize that referents are nothing but mental chatter, they dwell in mere mind appearing as such referents. This represents the four levels of the path of preparation. Subsequently, on the path of seeing, bodhisattvas directly perceive the dharmadhātu free from the characteristic of the duality of apprehender and apprehended. As for directly perceiving the dharmadhātu, having realized that there is no apprehended object that is other than mind, bodhisattvas realize that mere mind does not exist either, because without something apprehended, there is no apprehender.[56] Also Abhisamayālaṃkāra V.7 says on the culmination of the path of seeing:

If apprehended referents do not exist like that,

Can these two be asserted as the apprehenders of anything?

Thus, their characteristic is the emptiness

Of a nature of an apprehender.

The above two verses from the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra represent one of the classic descriptions of the "four yogic practices" found in many mahāyāna texts in general and Yogācāra works in particular. These four steps of realization are:

- (1) Outer objects are observed to be nothing but mind (upalambhaprayoga, dmigs pa'i sbyor ba)

- (2) Thus, outer objects are not observed as such (anupalambhaprayoga mi, dmigs pa'i sbyor ba)

- (3) With outer objects being unobservable, a mind cognizing them is not observed either (upalambhānupalambhaprayoga, dmigs pa mi dmigs pa'i sbyor ba)

- (4) Not observing both, nonduality is observed (nopalambhopalambhaprayoga, mi dmigs dmigs pa'i sbyor ba).